Author: Adam Simmons

Last updated: April 21st 2023

Introduction

For many people in the modern world the humble computer is an integral part of their everyday lives. It has moved away from being the extravagant luxury of the lucky few to an essential component of most businesses and a welcome addition to many households. Despite the increasing miniaturisation of the computer and the adoption of novel portable forms such as the Tablet PC and integrated ‘all in ones’ the raw power and versatility of the desktop PC is still unmatched. One key feature of the modern desktop PC that distinguishes it from these prescribed and fairly inflexible alternatives is the inclusion of a base unit (often a tower) with components which can be readily upgraded. Another distinction is the common inclusion of a standalone monitor, with a matte or glossy screen, which has undergone the same ‘evolution’ of the rest of the PC – and will continue to do so. Monitors are also popular partners for portable computers and increasingly games consoles, too.

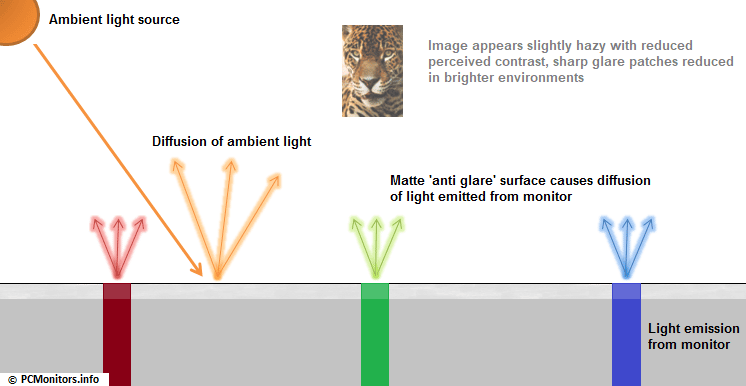

Although the intricacies of different display technologies are often misrepresented by manufacturers and poorly understood by consumers there is one fundamental attribute that is commonly discussed; the screen surface. In contrast with what goes on ‘under the hood’, the screen surface is readily visible on the outside and embodies the essential visual connection between the user and the monitor. Unlike the CRTs of the past, the modern display is not restricted by a hard and highly reflective glass surface. The nature of the screen surface is much more flexible and takes many forms – with varying degrees of anti-reflection or ‘glare busting’ properties. But as with most aspects of displays it is rarely that straightforward; there are certain caveats to the common ‘anti-glare’ surfaces. We explore the limitations of some of the more pervasive ‘anti-glare’ implementations and look at the alternatives and possible future direction of the computer screen surface. A matte screen surface comprises an outer polarising layer (or non-polarising layer for some screen technologies) that has been coarsened using mechanical and sometimes additional chemical processing. The common methods of manufacture of this surface include multi-layered ‘spluttering’ or several passes of ‘dip coating’ optionally followed by chemical surface treatments. Although it isn’t necessary to explore the intricacies of these coating processes we will consider the desirable end-result of this processing. This is to achieve a matte finish to the screen surface which acts to diffuse ambient light rather than reflecting it directly back to the viewer; a smooth surface acts a bit more like a mirror. The vast reduction of unwanted reflection and glare gives rise to a term synonymous with such a screen; anti-glare. Although the diffusion of ambient light and hence reduction of glare is desirable, it isn’t an infallible solution. The optical properties of the surface work both ways – that is to say that light emitted from the monitor is also affected. Furthermore there is some degree of interference between the emitted light and the diffused incident light. The path of both emitted (from the monitor) and ambient (from the environment) light and its interaction with the matte screen surface is shown in the diagram below. Whilst the desirable reduction in glare is achieved by the scattering of external light the image produced by the monitor is affected by the same diffusion process. The diffused ambient light also interferes slightly with the image produced by the monitor to exacerbate the process. The effects that this has on the image and the benefits attributed to the reduction of glare by a matte screen surface are summarised in the table below. Unlike the rough surface of a matte screen a glossy screen has a much smoother outer polarising layer (or non-polarising layer for some screen technologies). Rather than diffusing ambient light this smooth surface tends to reflect it back quite directly, causing unwanted reflections and sharp patches of glare – particularly under strong direct light. On the flip side the light emitted from the monitor is unhindered by a strong diffusion processes. And aside from reflections the image appears richer, more vibrant and unadulterated. Modern glossy films are often treated using an anti-reflective (AR) chemical coating such as magnesium fluoride or special polymers which act in part to aid absorption of some of the ambient light. Some of Samsung’s glossy models have their screen surfaces laced with silver nanoparticles in what is dubbed an ‘Ultra Clear Panel’. This is designed to aid absorption of some ambient light to a slightly greater degree than a traditional anti-reflective chemical coating without impeding image performance. The image below shows how the Ultra Clear Panel surface of a Samsung T27A950 and untreated glossy surface of a Dell Studio XPS15 laptop fairs on a fairly bright British summer’s day. The notion of British summer is not massively important in the context of this photograph, but it is to say it was nice and bright and even slightly sunny when the photographs were taken. But dull and rainy shortly thereafter. Light is coming in from a window to the right of the monitor but no direct sunlight is striking the screen. You can see in the image above that reflections are visible on both screen surfaces under such lighting conditions. The reflection is more intense on the Dell with a clear outline of the door, camera, cameraman’s hand and forearm and the red computer chair. On the Samsung these features are less well defined (obviously the chair is not visible at all as it is blocked by the laptop). Another observation is that the image on the Samsung appears richer whereas the image on the Dell appears bleached. Both screens were set to a brightness of 160 cd/m² and under dark viewing conditions the Dell’s image does not appear bleached in this way – this is caused by the fairly strong ambient light and is something that the Samsung doesn’t suffer from in the same way. Anti-reflective surfaces commonly used on laptops include and sometimes on larger screens include; Dell TrueBright, ASUS ColorShine, HP BrightView and Sony Xbrite. These produce a darker image upon reflection than the untreated Dell. Despite this slight reduction in reflections and darkening effect the Ultra Clear Panel is still very much a glossy surface. When displaying blacks and dark colours (or even light colours if ambient light is bright enough) reflections are still an issue and ambient lighting needs to be more carefully controlled. People may suggest that the brightness is turned up to help combat this, but the relative luminance of dark areas (particularly blacks) is considerably lower than bright areas regardless of the brightness setting. If it wasn’t clear from the mixed image above you will be under no illusion that this is anything other than a glossy screen surface when the monitor is switched off. This can be seen in the photograph below, which was again taken on a bright summer day. Note that the reflected image of the room on the Samsung is a little darker than on the Dell but objects still have distinct detail to them. Even though the reflection of ambient light can be reduced by the use of an anti-reflective or very slight anti-glare coating it is not completely eliminated, particularly where light is strong or the image is dark. If the monitor is set to a reasonable brightness, ambient light levels are relatively low and little light is falling directly onto the screen; reflections should not be an issue. Because the light emitted takes a more direct path and isn’t diffused by a matte surface you are left with a ‘cleaner’ and more vibrant image which can be fully appreciated under such conditions. The positive and negative attributes of a glossy screen surface are summarised in the table below. Some manufacturers offer a compromise between the two – a surface type that is sometimes dubbed ‘semi-glossy’ or that we’d usually classify as ‘very light’ matte. These surfaces are still matte but are roughened up either a little or a lot less, giving them a smoother appearance and making the diffusion of light weaker. They may have a somewhat reduced haze value, but we’d caution that specified haze values for monitors or the panel can be highly misleading and don’t really give you a good idea of what to expect from a screen surface. Having a ‘very light’ matte surface enhances the vibrancy and clarity of the image compared to a ‘stronger’ matte surface. But doesn’t quite bring the level of vibrant clarity or offer the same visual feel as a glossy monitor. Light from the environment that strikes the screen surface can provide what we sometimes refer to as a ‘glassy’ look, slight reflection of strong direct light or bright objects bathed in light. Light striking ‘stronger’ matte screen surfaces instead provides more heavily diffused glare patches, which are also undesirable as it can drown out or ‘flood’ the image. The image below shows the glare and reflective characteristics of a BenQ EW2420 with a ‘very light’ matte surface (rear) compared to a Dell Studio XPS15 laptop with a TrueLife glossy screen surface (front). This photograph was taken on a bright day during late spring with sunlight streaming in through the window to the right. You can see a clear and mirror-like reflection on the Dell laptop with the door, wall, chair and the laptop keyboard distinctly visible. On the BenQ you can see a fuzzy reflection of the door, the rear of the laptop and the cameraman’s hand. Once the screen is turned on these mild reflections aren’t an issue, unless particularly strong light strikes the screen directly. Which as we noted in the previous paragraph, is problematic even for ‘stronger’ matte surfaces. The image below shows the BenQ EW2420, under similar lighting conditions to the first photograph, displaying a mixed desktop background at 160 cd/m². You can no longer see the reflected objects on the screen. Samsung introduced a similar ‘very light matte’ screen surface to their SA850 series PLS (Plane to Line Switching) monitors which made use of a novel glass substrate processed to provide the aforementioned characteristics some way between ‘regular matte’ and glossy. Similar screen surfaces have been used on quite a few models now, as you’ll see from our review archive where we include a general classification of the screen surface. The image below compares the S27A850D (‘very light’ matte) to the Samsung 2030BW (‘regular’ or ‘medium’ matte) with both screens switched off. On the S27A850D you can see the outline of the windows facing the screen, whereas on the 2030BW you can see some slight glare at the periphery but no reflection. When the S27A850D is switched on to a reasonable brightness this generally isn’t an issue, as with the BenQ models. Some models, most notably from HP with their ‘Low Haze Enhancement’ treatment and various Philips models such as the BDM4350UC (below), use very low haze treatments typically around 1 – 5% haze. These provide an image that’s similar to a fully glossy solution, including giving that ‘wet look’ as ambient light strikes the surface, but with significantly reduced reflection. Note that the image below was taken in a bright room, but reflections appear quite soft. In somewhat dimmer conditions reflections that might remain bothersome on a ‘fully glossy’ screen are muted to the extent of becoming invisible and blending into the image. As explored in this article the reduction of glare and reflection on a monitor is a double-edged sword and must be finely balanced to avoid undesirable consequences. The ideal screen surface would be one which doesn’t interfere with light transmission, but at the same time is effective at reducing the impact of ambient light striking the screen surface. Back in 2003 optical film manufacturer MacDermid Autotype demonstrated a novel film coating that was intended to do just that. The film, which was co-developed with the Fraunhofer Institute of Solar Energy, was Dubbed Autoflex MARAG (MothEye AntiReflection AntiGlare). It was designed to mimic the tapered nanostructure of moth eyes (below) and the ability of these structures to maximise the harnessing of light with minimal reflection – as nocturnal moths need to operate in low light levels without light reflection on the eye surface giving away its position to predators. The film would apparently offer excellent image clarity comparable to current anti-reflective (glossy) surfaces whilst combating glare from all external sources, including direct sunlight. It was claimed that the outer surface would reflect under 1% of light – which is very impressive indeed. According to our communications with MacDermid Autotype the research and development for this particular MARAG film has been completed and a limited range of portable devices were released which used the technology in 2009. It was not seen in monitors. Other companies have also applied similar principles to create their own ‘moth eye’ films. The most notable is the filter used on the Philips 46PFL9706H, which was a premium 46″ LCD TV. Unfortunately the MARAG process which is apparently more intricate than ‘moth eye’ surfaces from other manufacturers were not a commercial success, owing largely to the high development cost of even small areas of such a film. The process could be applied to films which were 800 x 600mm and would be suitable for use on PC monitors. However; developing a film of this size with high surface quality at a competitive price was not possible. As a result, the MARAG film itself was discontinued as of 2009. But the company has continued developing a number of anti-reflective and low haze screen surfaces, using similar principles, which could be applied to monitors. Another excellent innovation which could lend itself well to computer displays has been developed by the Japanese company Nippon Electric Glass (NEG). The so-called ‘invisible glass’ consists of an extremely thin piece of glass coated on both sides with a highly efficient anti-reflective (AR) material. The material is layered with 30 ultra-thin film sheets, each sheet a few nanometres thick, and reportedly allows 99.8% light transmittance through the glass whilst reflecting a mere 0.1% of light on each side. This compares favourably to the 8% reflectance per side of a typical glass sheet and results in a piece of glass which, to all intents and purposes, appears invisible. When we contacted NEG about the technology back in 2011, they stated that it was undergoing further refinement before any sort of commercial availability is considered. The process was deemed too expensive for even relatively small sheets to be considered economically viable, let alone larger sheets that could be used on a computer screen. Such applications were and perhaps still are being carefully considered. So it is hoped that the layering process could be applied to something suitable to be used in a monitor. Light transmittance through the coating is excellent and once the materials and processes are refined there should be real commercial interest in this coating.

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases made using the below link. Where possible, you’ll be redirected to your nearest store. Further information on supporting our work.

Matte screens

Advantages of a Matte Screen Disadvantages of a Matte Screen Reduced glare can improve visibility of image in areas of strong direct or ambient light

Reduction in perceived contrast and colour vibrancy

Potential reduction in eyestrain in such circumstances as you don’t have to focus ‘through’ intense reflections or glare to see the image

Slight to moderate reduction in sharpness, depending on thickness and layering of matte surface Dust, grease and dirt less visible Generally more difficult to clean due to dirt penetration and relative difficulty seeing the fruits of your labour Grainy or hazy texture apparent in some instances, particularly when displaying white and other light colours

Glossy screens

A good example of a highly effective anti-reflective screen surface comes from Dell Alienware AW3423DW, the world’s first QD-OLED monitor. The image below shows the monitor displaying a desktop background of pure black in moderately bright daylight, with conditions controlled to avoid direct light striking the screen. Reflections are much more subdued than you’d expect under such lighting conditions and with such dark content. They can still be an issue in a brighter room, particularly reflections of brighter objects – and also if viewing the screen off angle where the curve tends to pick up and ‘stretch’ reflections across the screen. Examples of this screen under a range of lighting conditions are included in the review, towards the end of this section.

Some displays use a very mild matte anti-glare treatment for the screen surface. They have a very low haze value of around 2-7%. This describes the level of diffusion of light by the screen surface, with most matte screen surfaces having a higher haze value of ~25% or above. Such displays can therefore be classified as glossy or ‘close to glossy’ as their light emission and reflection properties most closely align with a glossy surface that has an anti-reflective film. The sort of treatment described above. In the past, some manufacturers (most notably Apple with their earlier ‘LED Cinema Display’ series) chose to forgo any anti-reflective treatment and included highly reflective untreated glass as the outermost surface. This was done largely for aesthetic reasons as there is no advantage of this over a properly treated anti-reflective surface when it comes to image quality. In general the amount of light reflected by any anti-reflective or very low haze surface is reduced compared to an untreated glossy surface and some form of anti-reflective treatment is now very common for glossy surfaces. The principle behind the glossy screen surface is explored in the diagram below, which considers both ambient light and the light emitted from the monitor itself.

Advantages of a Glossy Screen Disadvantages of a Glossy Screen Reduced diffusion of light across screen compared to matte surfaces reduces ‘hazy’ look in brighter rooms

Strong ambient light levels and direct light falling onto the monitor can cause troublesome reflections Easier cleaning due to lower dirt penetration and higher visibility of grease and dirt

Potentially increased eyestrain due to difficulty focusing on image through reflections

Generally greater aesthetic appeal – provided the screen is kept clean Dust, grease and dirt more visible – especially when the monitor is switched off. Routine cleaning necessary ‘Cleaner’ image without layering or graininess

Direct light emission enhances perceived contrast and image vibrancy

A half-way solution

It’s important to note that screen surface texture is also important and there are some models that buck the trends for ‘image smoothness’ expected from their haze values. Screen surface is a complex 3D structure with many layers and there’s a lot more to consider beyond a single haze value. Good examples would be some 23.6 – 27″ IPS-type ‘4K’ UHD (3840 x 2160) panels such as those used on the Dell P2415Q or ASUS PG27AQ. These are light matte anti-glare (relatively low haze value), which preserves image vibrancy and clarity, but don’t have a particularly smooth surface texture. This is quite apparent when viewing lighter content, as it appears grainy. Some models have relatively light-textured matte screen surfaces, even though the haze values (~25%) is shared by some models with noticeably grainier screen surfaces. We’d again caution against putting too much weight on haze values that may be specified for particular panels as that can be very misleading. Although 25% is often given as a ‘standard’ specification for haze value, there’s great variation seen in products which apparently share this specification.

Future screen surfaces

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases made using the below link. Where possible, you’ll be redirected to your nearest store. Further information on supporting our work.